Summer 2019 Seed Grant Funding Report

Submitted by Martha Olcott

The funding that I received from the Digital Humanities program helped support my attendance at the European Summer University in Digital Humanities at the University of Leipzig, where I completed the 2-week course on Humanities Data and Mapping Environments, and supported some of the cost of James Madison College student team members attending HILT course on Getting Started with Data, Tools and Platforms (which I attended along with Michael Downs and Bridget McBride), as well as ILiADS (which I attended along with Michael Downs, Sofia Cupal and Ryan Lumsden, and we were joined by a colleague from Harvard, Nargis Kassenova as well). In addition to the funds that I received from the DH program, part of the costs of this training was covered by James Madison College, and part was covered by my personal funds. In addition to some funding from JMC, I also helped support Michael Downs’ costs at ESU, where he also completed the course on Humanities Data and Mapping Environments.

The training that we received was really invaluable. At the end of the training at HILT we made the decision to develop a prototype of the website using a combination of two platforms (Esri Arcgis StoryMaps, and Omeka S). One of the major arguments for choosing StoryMaps (Beta) for our front end is that it has good Russian language compatibility. We also selected Abbyy Finereader for OCS because of the strong Russian language support and comparative accuracy,

We spent our time at ILiADS, where we worked under the direction of Jenna Nolt, a Librarian at Kenyon College learning to work with both StoryMaps and Omeka S. And by the time we left ILiADS we had done our first story, and we had begun populating Omeka S with our back-end materials, using Dublin Core for our meta-data. The students who attended ILiADS all continue to work on the project, and have responsibility for specialized tasks (Sofia Cupal for Omeka (and has already trained an “assistant” to work with her)

While at ESU we learned more about other mapping options for the project, which we are likely to try and implement at later phases of the project, assuming we continue to be able to grow the project. We plan to continue to use the current combination of platforms for another 6-18 months, depending upon our speed of progress in populating the back-end archive and whether we are successful in our efforts to secure enough funding to allow for expanding our student led team and to pay for some advice from a professional web-site developed.

While our plans could obviously change, for now we are thinking that our intermediary stage should involve migrating the project fully to Omeka-S, with a front-end designed with some outside advice. We think that this would make the site more user friendly once we begin our crowd-sourcing efforts. And if we are able to develop a readership for our site through crowd-sourcing, then we would hopefully be able to attract enough funding to hire a developer to help us rebuild and relaunch the site using a platform of our own creation that would meet the unique needs of our project.

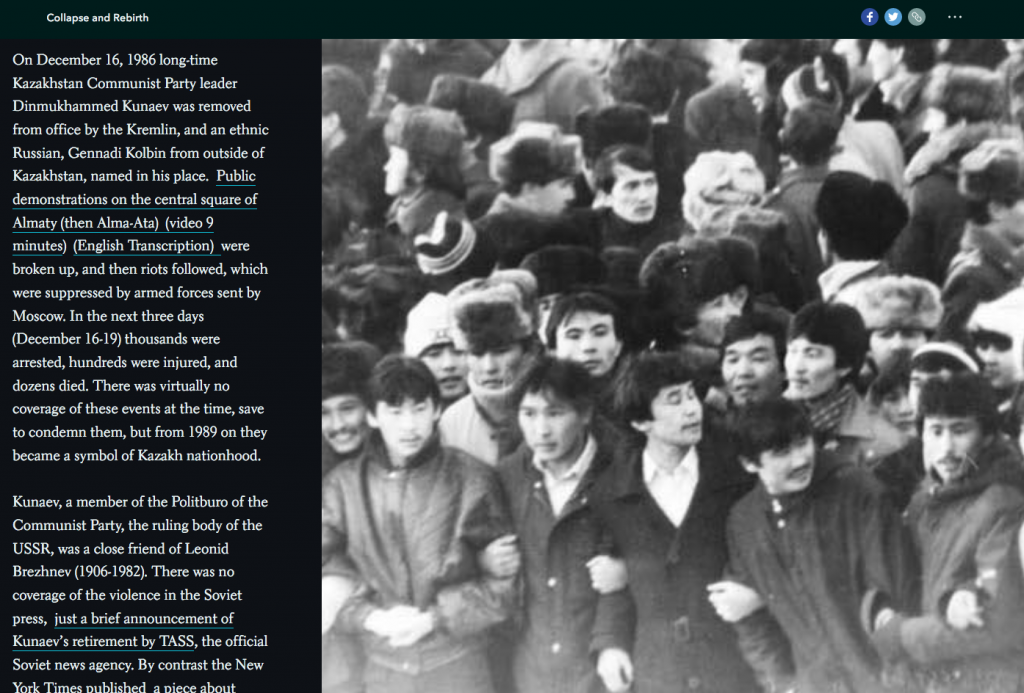

For now the combination of Story Maps and Omeka-S is working well for us. I was able to present this first story at ESU, where I showed our first story on “Zheltoksan: The December Events in Kazakhstan (1986).” While at ESU I also was a speaker on a panel discussion on “Responsibilities of Digital Humanities.” My time at ESU was also very beneficial in helping me develop contacts with people working in the area of digital humanities in Russian language contexts. I hope to continue to expand these contacts during my planned stay at University College London School of Slavonic and East European Studies where I have been awarded a 3-week visiting fellow slot to work on this project in February-March 2020.

I currently have a team of 10 students working with me, including 2 sophomores and 3 juniors, and we will try and recruit more sophomores and juniors during spring semester as we begin to phase our seniors out. Each brings language or technical skills, and some bring both. We hold team meetings each Friday, and my JMC office has been turned into something of a laboratory, with our IT person giving us 3 additional computers, a scanner and a printer (as well as a number of office keys allowing for individual team member access). We also have created a 10 member advisory board, who we try to at least periodically apprise of our progress.

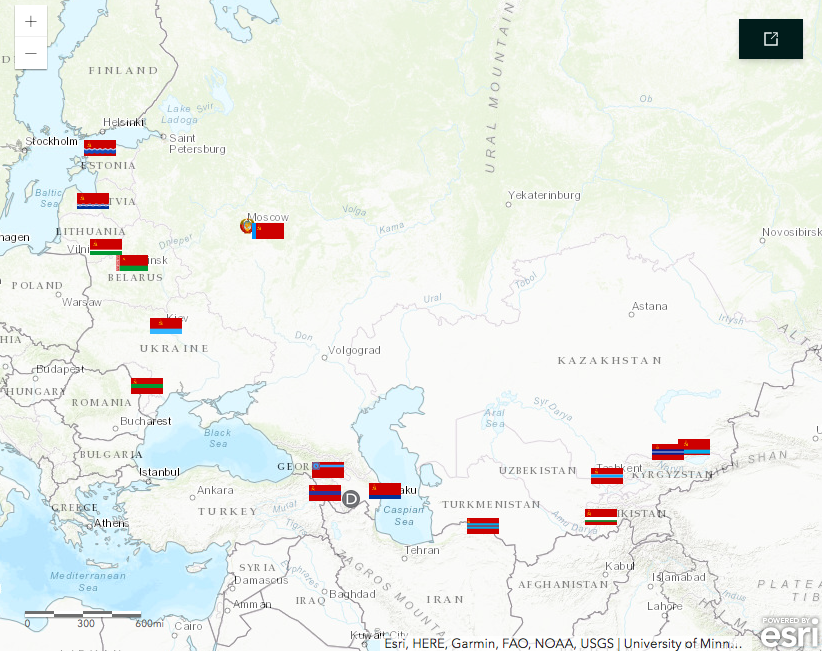

We currently have a prototype that includes a main narrative story, and the beginnings of 15 separate stories (one for each Soviet republic), all supported by the same Omeka-S backend. Our goal will be save all of the stories by republic in their respective republic “stories” including those that we have singled out as of particular importance which are in our main narrative as well.

A group of 7 students travelled with me to the Central Eurasian Studies Society annual meeting in Washington DC, where we presented our current prototype on October 12, 2019. The presentation they gave is available here.

The website opens with video of Mikhail Gorbachev’s announcing the end of his rule and of his country, followed by an introductory narration and 5 key events in the history of the period: “The December ‘Zheltoksan’ Events” (Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1986);“ The April 9 Tragedy” (Tbilisi, Georgia, 1989); “The Fergana Events” (Uzbekistan, June, 1989); “Black January” (Baku, Azerbaijan, 1990); and “The January Events” (Vilnius, Lithuania 1991).

We are hoping to do more different kinds conference presentations over the next 7-8 months. We have applied to do a poster and a lightening talk on the fight for national language rights at DH 2020 in Ottawa, and are applying to also present some of this material at MSU’s Global Symposium in March. And the students are applying to do a panel at an undergraduate session that is part of the Midwest Political Science Association meetings in April. The presentation at this meeting will focus on materials from the Congress of Peoples’ Deputies, a partially popularly elected body that both served as a platform for democratization and also hastened the USSR’s demise through the revelation of the deep fissures within the country. We hope that this will serve as a prototype for a presentation in August 2020 at the International Council for Central and East European Studies in Montreal.

In addition we continue to digitize archival materials and narratives for a number of other key localized events with long term impacts including: Novyi Uzen riots (Kazakhstan, June 1989); Kishinev events (Moldova, November 1989); Dushanbe Protests (Tajikistan, February 1990); and the Osh events (Kyrgyz Republic, June 1990). Finally we are developing narratives that link to existing resources (included in Appendix X) which highlight the ‘Baltic Wave,’ a human chain joining peaceful demonstrators in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, on 23 August 1989, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Ribbentrop Molotov Pact. We also are digitizing materials on

Karabakh Conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan (1988- 1994, when a cease fire agreement was signed); Georgia’s conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia; the Conflict in Chechnya (1991-1994, also known as the First Chechen War); Tajikistan’s Civil War (1992-1994, though fighting continued until the National Reconciliation Agreement in 1997); and Transdniestria’s War (Moldova 1990-1992).

In addition we are doing bibliographic work to link our project to existing websites and digitized materials on early political movements in the national republics: the Popular Front of Estonia (1988-1993), Sajudis (the Lithuanian movement 1988-1990), and the Popular Front of Latvia (1988-1990); in the Western Republics: the Popular Front of Moldova (1989-1990), Belorussian Popular Front “Revival” (1989-1993) and “Rukh”, Ukraine (1989-1990) and its Human Chain connecting Kyiv to Lviv in 1990; the Roundtable – Free Georgia” alliance (1990-1993), the Armenian National Movement (started 1990), and the Popular Front of Azerbaijan (1989-) in the South Caucasus; and Nevada-Semei anti-nuclear movement (Kazakhstan, 1989-1991), the Democratic Movement of Kyrgyzstan (1989-1990), the United Tajik Opposition (during Tajikistan’s Civil War) and the Birlik and Erk movements in Uzbekistan. We are also looking at materials on the economic and environmental catastrophes that increased the public’s sense of government incompetence (such as Chernobyl in 1986, or the Armenian earthquakes in 1988, which spurred different kinds of political protests, including industrial strikes.

We recognize that we can’t do everything at once, hence our interest in slowly chipping away at the materials we have at our disposal, working with members of our advisory to try and identify and “save” appropriate materials for future digitizing. And we intend to keep trying to arrange conference presentations of our work, to maintain a strong incentive system.